Marine insurance provided a means by which merchants could manage the risks of their business and share those risks - and part of the returns - with a much wider group of domestic and international individuals.

Marine insurance thus facilitated the ‘expansion of Europe’, the explosion of European traders, soldiers and colonists into the wider world from the 15th century onwards who established new empires for the major European powers and ultimately founded a global system of capitalism.

Marine insurance therefore predated the era of British colonial slavery (which began c. 1625), but the rise of Lloyd’s from the original coffeehouse (1688/9) to the establishment of New Lloyd’s (1771) and the subsequent consolidation of its position as the leading market for marine insurance coincided with the emergence of Britain in the 18th century as the largest slave-trading power and the development of the British transatlantic colonies as a major slave-system.

From 1720 onwards, only two companies (the London Assurance and Royal Exchange) could underwrite marine insurance in Britain: the rest of the market was made up of individuals, for whom Lloyd’s played a critical role as a platform to operate within a framework of rules and practices.

The slave-economy was one of the major markets for British marine insurance. Most of Britain’s trade was with Europe, and the majority of policies by number were almost certainly for European and coastal voyages. But the premia were higher on long-distance voyages, those to Africa, the East Indies and the Americas, so in financial terms these lines of insurance predominated. The slave-economy was clearly a principal feature in the British financial construct and by extension also significant to its marine insurers.

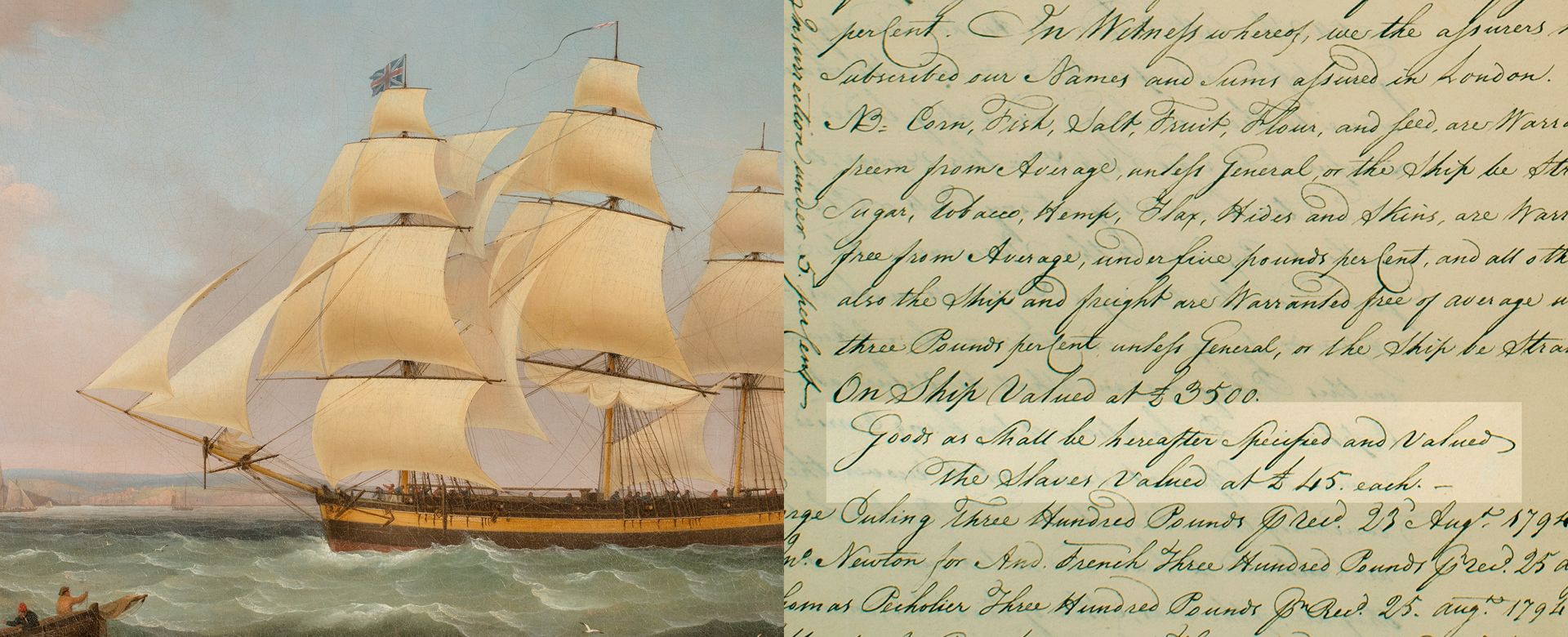

Originally, the pattern of organisation for commerce built on slavery was truly a triangular trade, a single ship leaving Britain carrying goods for exchange on the west coast of Africa, carrying the captive Africans purchased there across the Atlantic on the ‘Middle Passage’, and selling the survivors in the Americas in exchange for slave-grown produce, especially sugar and tobacco but also rum, coffee, indigo, spices and mahogany, which were brought back to Britain to fuel the consumer revolution of the eighteenth century. But as the system grew, the triangular trade became more of a metaphor. The slave-ships still fulfilled the first two legs, but often came home in ballast, while an important bilateral trade between Britain and the trans-Atlantic colonies developed, shipping plantation supplies to the colonies and returning with slave-grown produce in custom-built ‘West Indiamen’, ships capable of carrying far more cargo than slave-ships.

It is estimated that slavery-related business overall accounted for between one-third and 40 per cent of premium income in the second half of the 18th century. The insurance of the slave-voyages themselves accounted for an estimated 5-10% of total marine insurance premia. Of more financial importance to the insurance business were the ships sailing directly from Britain to the Caribbean and back, accounting for some 30% of total marine insurance premia paid.

Only fragmentary records exist for the marine insurance business of the eighteenth century outside the two incorporated firms. What does exist tends to support the view that the composition of the business done at Lloyd’s was not materially different from the marine insurance market as a whole, of which Lloyd’s came to make up an increasing share.

One index of the overlap of Lloyd’s and slavery is the analysis of the list of named subscribers to New Lloyd’s in 1771. Of the 77 surviving names, at least eight are known to have invested directly in slave-trading voyages, while a further seven were themselves slave-owners or lenders or annuitants secured on enslaved people .

The British slave-trade ended in 1807. British colonial slavery itself was abolished only in 1834. Lloyd’s entanglement in slavery did not end with Britain’s abolition of slavery. Cotton grown by enslaved people in the southern United States became a key driver of Britain’s industrialisation from the 1790s onwards, and the insurance of the shipping of raw cotton to Britain and of manufactured cotton products to markers worldwide remained an important part of Lloyd’s business, until the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865 and in South America, with Brazil in 1888. The legacies of slavery in the colonial systems have continued to the present day.

Lloyd’s is not alone in beginning only recently to come to terms with its historical connections to slavery. The insurance of slave-ships and, under complex policies, of the captive Africans on board them, however, has an especial resonance and entails a specific responsibility of acknowledgement and repair, of which this fact sheet is one small part.