This research project brings together data that helps us to understand and acknowledge the role of transatlantic slavery through significant members of Lloyd’s history. It traces the links to the slave trade, the wider slave economy and slave-ownership of the founding subscribers of Lloyd’s New Coffee House.

This ongoing research has been facilitated by a partnership with Professor William Pettigrew, University of Lancaster, who is the Principal Investigator of the Arts and Humanities Research Council funded Legacies of the British Slave Trade: The Structures and Significance of British Investment in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 1550-1807, whose database of British slave traders will be published as The Register of British Slave Traders, in 2024. Darcy Beckett, an MA student at University of Lancaster, provided the initial research on Lloyd’s founders who appeared in The Register of British Slave Traders. Dr Nick Draper, who is working on the London slaver traders for The Register of British Slave Traders has also generously provided essential further research. We are grateful to Professor William Pettigrew, Dr Nick Draper and Darcy Beckett for their support and assistance.

New Lloyd's Coffee House

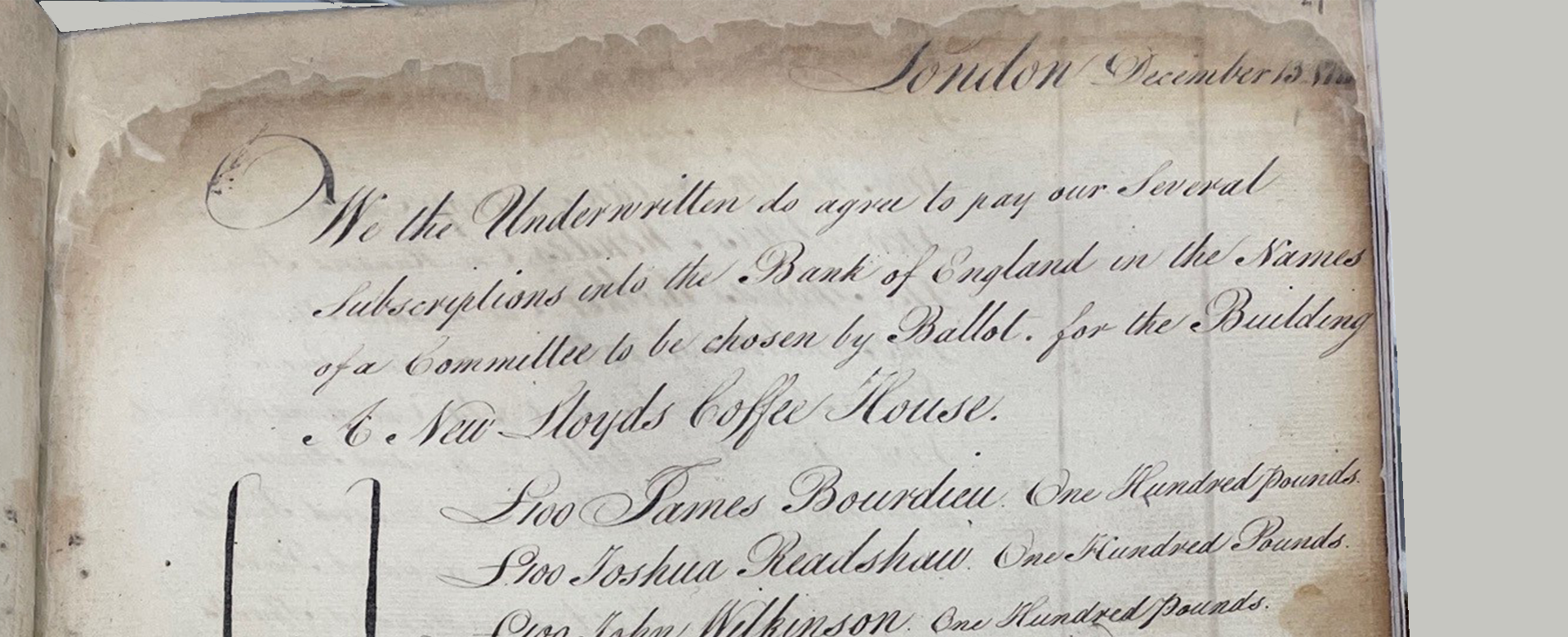

In 1769 a group of merchants, brokers and underwriters moved their business from Lloyd’s Coffee House in Lombard Street to ‘New’ Lloyd’s Coffee House at 5 Pope’s Head Alley. This was to distinguish themselves from the ‘shameful practices … such as Speculative Insurances on the Lives of Persons and Government Securities… it is notorious they are calculated for the purposes of Stock-jobbing, and tend to weaken Public Credit.’[1] On 13 December 1771, 77 of these men subscribed £100 each for the ‘Building of A New Lloyd’s Coffee House’. The original list of founders forms the first entry of the Minute Books, and is part of a series of records that continues through to today.

Although, Edward Lloyd set up his Coffee House in the late 1680’s there is no archive which survives that provides evidence of its activities until the foundation of New Lloyd’s Coffee House. The formation of this group signalled a change from a loosely connected set of people related to marine insurance meeting and transacting business in a coffee house, to a system of membership through subscription. New Lloyd’s Coffee House was run by a ‘Committee for the Management of the Affaires of this House’. In the early minutes there are no records of an official election of a Chairman but a Committee member was ‘in the Chair’ for every General Meeting of Subscribers. It was not until 1811 that an annual election of a Chairman and a Committee was inaugurated.

[1] Part of the resolutions passed by New Lloyd’s in March 1774, Lloyd’s Minute/Subscriber's Book, Ms 31571-1, Guildhall Library

The founding subscribers of New Lloyd's Coffee House

77 founders’ names are extant in Lloyd’s Minute Books. In 1876, Frederick Martin claimed in his history of Lloyd’s there were 79 founders. Of Martin’s two additional founders, one of these had his name ‘burnt out completely’ and is unknown and cites the other as John Julius Angerstein. In a note, Martin asserts that Angerstein’s ‘name was barely to be deciphered, standing at the top of a page burnt away at the edges in the fire of 1838.’[2]

No evidence now survives of either Angerstein or the other unknown name being founders of New Lloyd’s Coffee House.

[2] Frederick Martin, The History of Lloyd’s, 1876, London, Macmillan & Co. p.147n.

A note on terminology

UCL’s Legacies of British Slavery database published in 2009 provided a dataset of British subjects who were owners of enslaved people and allowed the wider public to understand the concept and impact of British slave ownership. However, this is only one aspect of Britain’s involvement with transatlantic slavery.

Although most people will understand that a slave trader was a man who profited from and traded in enslaved Africans, Lloyd’s Collection and history present a more complex network of individuals who were financially enabled and profited from the slave trade and the wider slave economy. Beyond the trade in people, the goods produced by the enslaved and the goods coming from Britain to support the operations of the plantations created a wider and thriving slave economy which was central to the financial infrastructures of the City of London and growth of the British Empire. Additionally, professions were more fluid in the 17-18th centuries and networks extended across the City of London and into Parliament, to support the systems of trading as part of the slave economy.[3]

However, the lexicon does not currently exist to describe those iterative economic networks and categories of implication in both slave trading and the slave economy. Transatlantic trading was high risk and without the underwriters, brokers and merchants who took on that risk, most of it would not have happened. However, technically, the underwriters and brokers of slave voyages were not slave traders, even though some engaged in slave trading separately. This is why more encompassing terminology has been used to denote Lloyd’s founders links to the slave trade or the wider slave economy.[4]

[3] Nick Draper, ‘The City of London and slavery: evidence from the first dock companies, 1795-1800’, Economic History Review, 61, 2, 2008

[4] I am indebted to Dr Alexandre White, who has generously discussed these and other ideas with me throughout the independent research collaboration between Lloyd's and Black Beyond Data based at Johns Hopkins University.

Download the research findings factsheet

This factsheet details the research findings. The list of the 77 founders is divided into the following four sections, in alphabetical order.

- Founders with links to the slave trade

- Founders with links to the wider slave economy, including slave ownership

- Founders with potential links to slavery but unconfirmed

- Founders with no confirmed links to slavery