The top risks in shipping today

Carrying 90% of world trade, the shipping industry forms the backbone of the global economy. We explore some of the biggest threats to the sector with insight from Lloyd’s market marine experts.

Shipping can be a risky business. Today, when things go wrong at sea, the prospect of successfully salvaging an ultra large vessel is anything but simple. It is a feat of engineering made more complicated by the increasing size of vessels, glare of public opinion and increasingly stringent environmental rules.

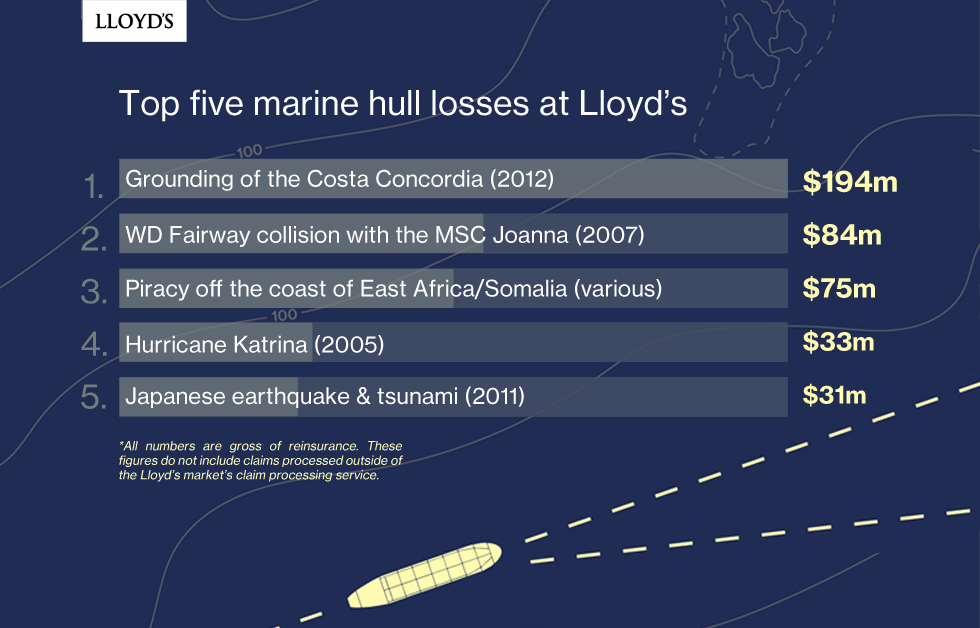

The tragic story of the partial sinking of the cruise ship Costa Concordia in 2012 and grounding, break-up and sinking of container carrier Rena in 2011 highlight how costs can escalate. The ensuing salvage operations for both losses ended up costing insurers many multiples of the hull values due to the unique circumstances of each incident and environmental sensitivities.

Elsewhere at sea, agents of instability such as seaborne cyber attackers and other pirates threaten lives and to disrupt the flow of international trade and commerce. If that weren’t enough, the shipping industry marches towards automated shipping with all the complexity that it entails. And ship captains are expanding the frontiers of risk as they venture further north in search of new navigable seaways. But who will be the first to suffer a casualty and pollute the pristine Arctic, with all the environmental damage and negative publicity that is likely to ensue.

In this context, it’s worth remembering that 90% of world trade is still carried by the shipping industry, forming the backbone of the global economy. With insight and input from marine insurance professionals across the Lloyd’s market, we explore the top risks in shipping today (these are presented in no particular order of priority).

A cyber-attack that sinks a ship or ships

The threat of a cyber-attack is a hot topic, says Neil Roberts, Manager of Marine and Aviation at the Lloyd’s Market Association. “It’s the new piracy and it is generating a lot of heat and noise at the moment, but very little light.”

As much as any other industry, operators are dependent on the computers aboard their ships. However, one factor that provides a measure of resilience is the fact that many of these on board computer systems are self-contained. They aren’t typically connected to the World Wide Web, which makes it harder for would-be hackers to infect from the outside.

Ship owners do still have their concerns when it comes to cyber, says Roberts. “Usually the threat comes from an insider or a disgruntled employee,” he says. But sea captains aren’t completely immune to attacks from outside as an experiment in 2013 showed. A research team from the University of Texas successfully spoofed a ship’s GPS-based navigation system sending the 213-foot yacht hundreds of yards off course – without triggering any alarms.

But the big question on many people’s minds, says Roberts, is whether or not a cyber event could cause a ship or worse, multiple ships, to sink. He says there’s not currently enough understanding of the difference between what’s theoretically possible and its likelihood – and fear of the unknown is a concern for many.

The rise of autonomous vessels

The shipping industry expects widespread adoption of autonomous vessels over the next few years. There is increasing demand for cutting edge technology for unmanned boats and submarines, part of a growing £100 billion global industry, according to the UK government. Meanwhile plans are afoot to operate the world’s first fully electric and autonomous container ship, with zero emissions. The Yara Birkeland is expected to launch in Norway next year. Its arrival could be a huge turning point for the global shipping industry.

“We are working hard to understand what might happen with autonomous ships,” says Roberts. “The technology is moving faster than the regulations. And before that regulatory change happens it’s difficult to see autonomous ships taking off in a big way. At the moment there must be a human master at sea.”

From an insurance perspective, he says, these risks aren’t particularly new. Remote underwater vehicles have been used for some time, he says, in wreck diving, for example. He takes a pragmatic approach. “If you’re insuring an asset, then the asset is the same whether there’s a crew on board or not. The question is: does getting rid of the humans make it more or less safe? We know that there are many times when human intervention has led to collisions being avoided.”

Exploring the high north

Traditionally the Arctic has been largely off limits for most merchant seafarers and marine insurers alike. However, as the polar regions are increasingly opening up for tourism, exploration and commercial operations, the market is receiving more enquiries. “This is at the new frontier of risk,” says Roberts. “Within the Lloyd’s market there are specialist underwriters who will consider coverages for ships that specifically want to take Arctic sea routes.” The “salvage gap” however, remains a big concern for underwriters. “There are very few salvage options in the high north.”

Earlier this month a liquefied natural gas carrier, Christophe de Margerie, set a new time record for transiting Russia’s northern sea route. The Russian state carrier said the vessel spent 12 hours and 15 minutes in the northern sea route without any escort icebreakers – the first merchant vessel to do so.

“No ship captain wants to be the first to pollute the pristine Arctic ocean,” says David Lawrence, Controller of Agencies at Lloyd’s. “Protecting polar waters and the people who live in these extreme environments is paramount.” A useful development in this area, he says, is the Polar Code, an international code of best practice for ships operating in the harsh environment of the waters surrounding both poles, which came into force in January 2017. A key element is the requirement for any ship operating in polar waters to have in place robust contingency plans covering navigation, pollution incidents, a ship’s structural requirements, and search and rescue plans.

A return to piracy

Roberts takes a long view. “Piracy is the direct result of social conditions. Provided the opportunities and means are present someone will always do it. It’s like a balloon. If you squeeze it in one place it pops up in another.”

Around the turn of the decade the coast of Somalia became notorious for the frequency of its pirate attacks. The conditions in this part of the world – which included severe political instability in a country that bordered one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes – led to a series of hijackings. In 2010, Somali pirates hijacked 49 ships and took over 1,000 hostages, according to the International Maritime Bureau.

“It was the focus of the world’s attention for some time,” says Roberts. “And in response ship owners got together and produced self-defence guides, some started hardening their ships with water cannons and others employed armed guards. In addition a transit corridor was set and many countries contributed naval support. Many of the ships that did get attacked were deficient in at least one of these areas in some way. But it was enough to hold the situation. Now that uneasy truce is gradually being eroded and there have been some close calls recently. Nobody knows what will happen when the naval support is withdrawn at the end of next year.”